The History of HIV Cure Research: Reaching for a Cure

Contributing Author: Gina Hagler

A new immune deficiency illness came on the scene in 1981. In the years immediately following, four questions arose that indicated the uncertainty of the time: What was this illness? How was it transmitted? Could it be treated? Could it be cured? By 2004, when the number of people living with what we now knew as HIV had risen to its highest level, three of those questions had been answered: The illness was a retrovirus. Transmission occurred most commonly through sexual behaviors and needle or syringe use. A daily cocktail (combination) of antiretroviral therapy (ARTs) could stop HIV from progressing to its deadly form (AIDS).

Today, the daily use of ARTs for HIV treatment has made what was once a death sentence into a chronic illness. Yet, prolonging the life of those infected is not a cure. As the search for an HIV cure continues, four new questions related to the search have arisen: Is a cure possible? Are there viable cure strategies? Do we still need a cure? Are we any closer than in 2004?

Is a Cure Possible?

There are two cases in which HIV-infected individuals have been cured. Both cures were achieved as the result of treatment for a condition other than HIV. The first cure was announced in 2008. The first person, Timothy Ray Brown aka the “Berlin Patient,” had received two bone marrow transplants to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The stem cells were from a donor who had inherited the same alleles for the CCR5--Δ32 mutation. The authors of a 2017 peer-reviewed article in BioMed Research International, Advancements in Developing Strategies for Sterilizing and Functional HIV Cures, wrote that the CCR5--Δ32 mutation “renders cells highly resistant to HIV-1 infection.” The authors continued, “Eight years after treatment, he “appear[ed] to be free of both HIV and AML. However, it is very difficult to find donors with human leukocyte antigens (HLA) identical to those of recipients for CCR5--Δ32 stem cell transplantation, while the mortality rate of transplant surgery is up to 30%.” It is this mortality rate, as well as the possibility of host vs. graft disease that makes stem cell transplants an unrealistic avenue for an HIV cure.

Credit: Heidi Schumann for The New York Times Timothy Ray Brown

Are There Viable Strategies?

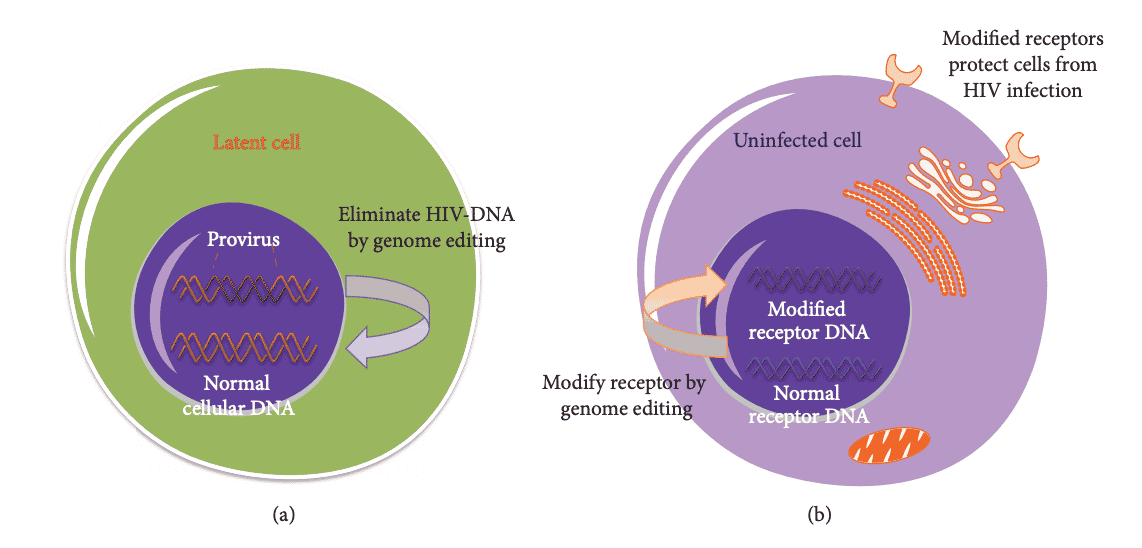

Webster’s Dictionary defines cure as “a healing or being healed; restoration to health or a sound condition.” It mentions nothing about the strategy for achieving a cure. Two strategies for a cure today are sterilized and the functional cure. With the sterilized cure, all traces of HIV are absent; No disease remains in the patient, in a latent reservoir or otherwise. With the functional cure, modified receptors protect cells from HIV infection; The infection is still present, but it is present at levels below detection or transmission. In Advancements in Developing Strategies for Sterilizing and Functional HIV Cures, the authors identify the key obstacle to an HIV cure as the latent HIV reservoirs, mainly composed of resting CDR+ T cells in the early stages of HIV infection. The figure below illustrates the sterilized cure (a) in which the HIV reservoirs are eradicated, and there is “the complete elimination of replication-competent proviruses.” “Functional cure refers to the long-term control of HIV replication, which involves maintaining a normal CDR+ T cell count and HIV replication below a detectable level,” represented by (b) with the prevention of susceptible cells from HIV infection.

Hindawi: BioMed Research International Volume 2017, Article ID 6096134

A third strategy is described in an article at NIH/NIAID, Sustained ART-Free HIV Remission. Sustained ART-free remission would not involve eradicating the HIV reservoir but would allow a person living with HIV to keep the latent virus suppressed without daily medication. Most approaches under investigation include altering the immune system to induce long-term control of HIV. Researchers are attempting to achieve their goal by manipulating the immune system with interventions that target HIV and HIV-infected cells or change the behavior of immune cells as they try to address the infection more effectively.

Do We Still Need a Cure?

The widespread use of ARTs to control HIV infection makes it possible for those who would have died within eight to ten years of an HIV diagnosis to live for decades. This reality leads some to question the need for a cure. Wouldn’t HIV prevention be sufficient? The question is a good one, however, living with HIV is not the same as having a cure for HIV. ARTs are a toxic cocktail of drugs, which must be taken every day, with long term side effects including heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, and bone wasting. This reality leads others to question how we can not pursue a cure.

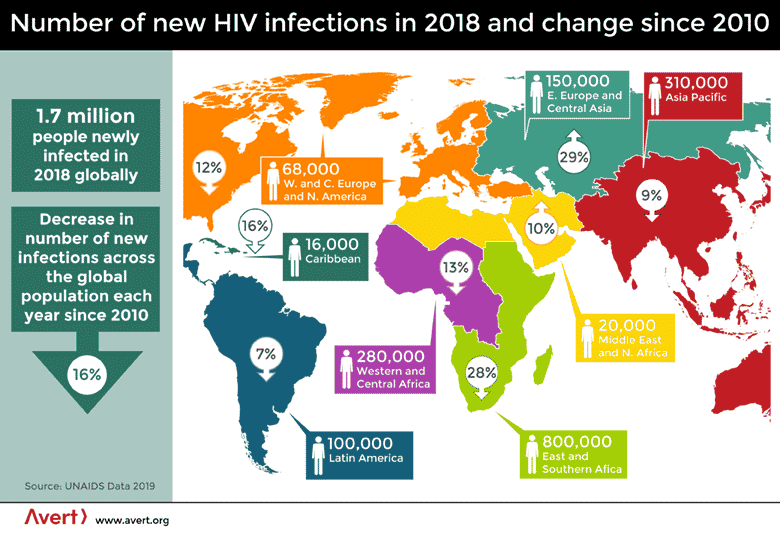

The role played by ARTs cannot be overlooked. Their daily use by millions of infected people has reduced the number of new infections across the population since their global use began in 2010. Yet, there were still 1.7 million people newly infected in 2018 worldwide. In the East and Southern African countries lacking adequate healthcare or health-related information, they still average 2,000 new cases each day. Millions of children have lost one or both parents to this disease with no end in sight.

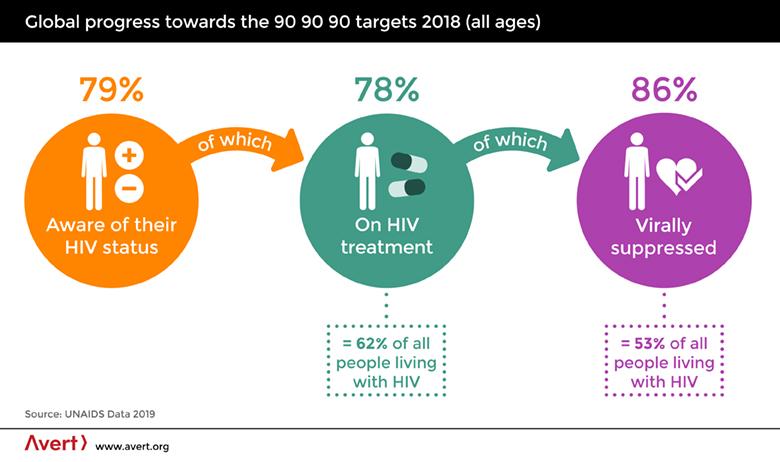

To stem the tide of HIV infection, UNAIDS has instituted its 90-90-90 targets. Since the stigma of HIV diagnosis leaves people reluctant to be tested - a fatal misstep since there is no treatment without a diagnosis - the first of the UNAIDS targets addresses this directly by calling for widespread testing to make 90% of the population aware of their HIV status. The next target is for 90% of those with an HIV diagnosis to receive treatment with ARTs. The final target is for transmission of the virus to be suppressed through the daily use of ARTs in 90% of those treated with ARTs.

The ability to prolong the lives of the 37 million people already infected with HIV/AIDS while reducing transmission of the virus meets the goal of limiting new infections. Perhaps it will even lead to the eradication of the virus for all practical purposes. However, to improve the quality of their lives requires a cure.

Are we any closer to a cure than we were in 2004?

Researchers are pursuing several strategies. As a result of the London Patient’s cure, some researchers are capitalizing on the use of stem cells from those naturally resistant to HIV. A strategy along a similar path uses antibodies from the same “elite controllers.” A third possibility is the “kick and kill” strategy in which the latent virus is first awakened and then killed. “Latently infected cells appear identical to uninfected cells, so there is no way [for the body] to distinguish between the two,” said Professor John Frater of the University of Oxford in a 2019 article in The Guardian. “But if those cells start to express viral proteins on their surface, they become a target.” Advances in research have brought about additional possibilities with existing strategies while bringing us closer to a cure.

Conclusion

We now have answers to the four questions related to our current pursuit of an HIV cure. Yes. Researchers have seen that a cure is possible. Yes. There are at least two viable strategies, as well as the possibility of sustained ART-free remission. Yes. We still need a cure because ARTs are to those infected with HIV as insulin is to those with diabetes. Only a cure will make it possible for those infected with HIV to lead a normal life. Yes. We are closer to a cure than we were in 2004.

Take away:

Could AGT have the Long-Awaited Cure?

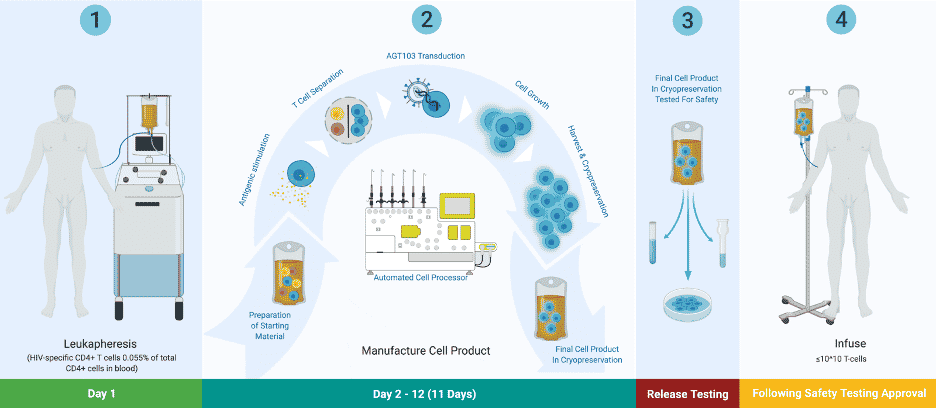

American Gene Technologies (AGT) is determined to restore active HIV immunity to individuals infected with HIV. To that end, they have developed a promising approach. In 2016, AGT met with the FDA to propose a new approach for treatment.In 2019, AGT submitted an Investigational New Drug (IND) application to the FDA, seeking approval to begin a human trial.

In 2020, NIAID repeated AGT’s approach to a functional cure for HIV/AIDS.. Researchers at NIAID were able to replicate AGT’s results. Their findings are documented in a peer-reviewed article co-authored by AGT and published in the May issue of Molecular Therapy. AGT recently began its Phase 1 study. The clinicaltrials.gov identifier number is NCT04561258 and the study ID is AGT-HC168. For information about the ongoing Phase 1 study of AGT103-T, and information on the trial sites, click here.

AGT Founder and CEO Jeff Galvin describes what AGT’s trial will accomplish as “isolating HIV T-cells in somebody's body to make them immune to HIV…. I'm improving the function of those cells, so they're able to clear HIV without becoming infected, just the way your cold T-cells can clear a cold without becoming infected by the cold, which is the key to clearing this pathogen? It’s that simple.”