The History of HIV Cure Research: Discovery to Treatment

Contributing Author: Gina Hagler

When reports of a new immune deficiency disease hit the news in the summer and fall of 1981, the cause and method of transmission were unknown. At first, it seemed this new disease only affected gay men and, as a result, what is now known as HIV/AIDS was viewed by many as the consequence of a gay lifestyle. Researchers soon found that the HIV virus was a sexually transmitted disease that could infect partners of either gender. When experience showed that the virus could also be transmitted through organ donations and the blood transfusions those with hemophilia needed to survive, the public reacted with fear. They insisted that people who were infected be kept away from those who were not. The federal government passed legislation that protected the rights of those infected with HIV. The U.S. government also invested in HIV cure research, as did private individuals.

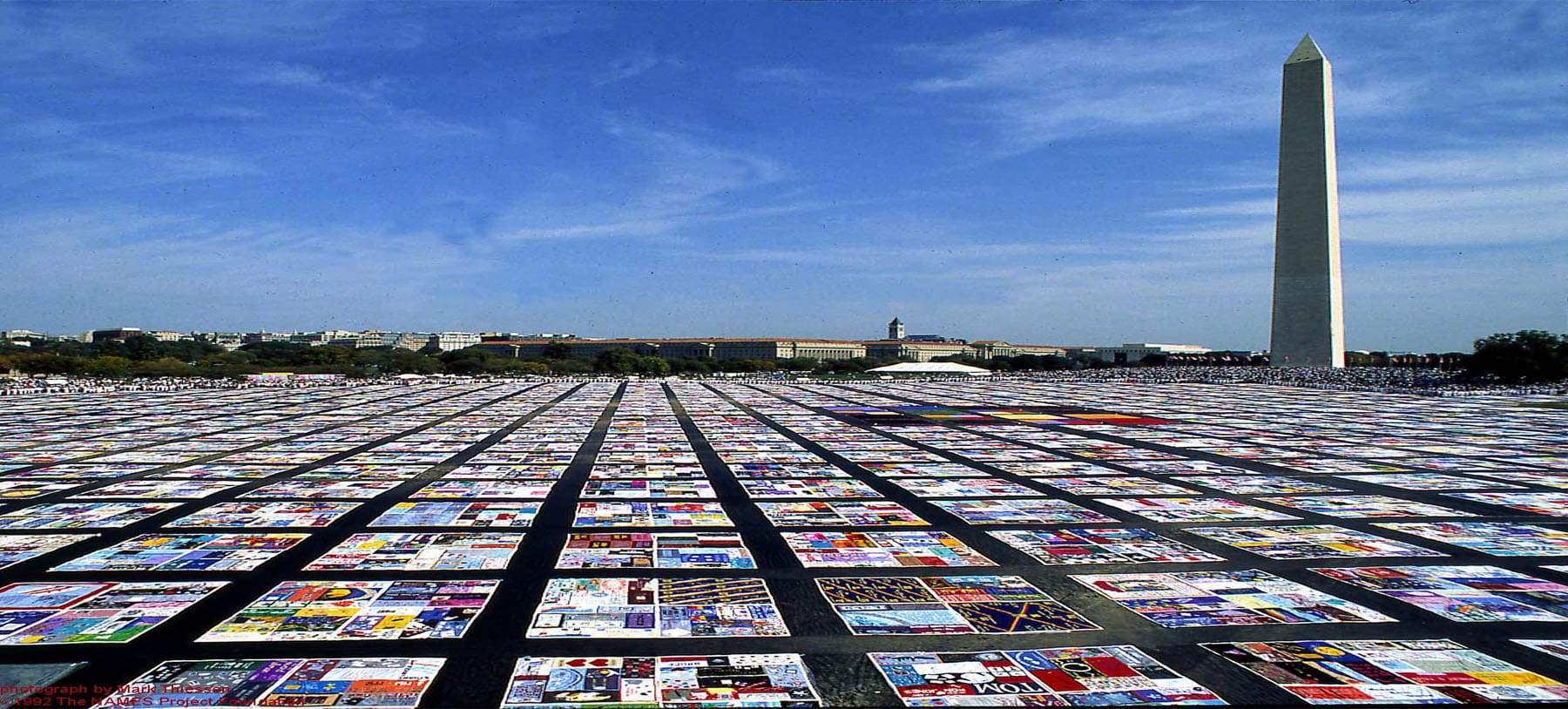

Each square on the AIDS Memorial Quilt represents one person who has died of AIDS.

Photo Credit: National Institutes of Health

The CDC announced the major routes of transmission for HIV in 1984. The cause of the virus was identified the following year. By 1996, a “cocktail” of drugs that halted the progression of the HIV virus before it developed into AIDS was being used to treat patients. These antiretrovirals prolong life, but they are not a cure. To date, AIDS has taken more than 30 million lives worldwide. As AGT begins its trial for a cure for HIV/AIDS, here’s a closer look at the history of HIV cure research from the first days of HIV to the development of the antiretrovirals in use today.

Sounding the Alarm

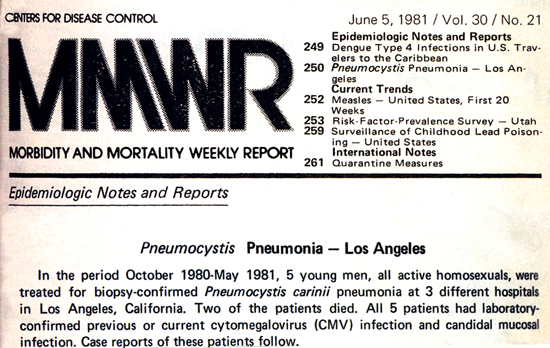

The CDC announced the major routes of transmission for HIV in 1984. The cause of the virus was identified the following year. By 1996, a “cocktail” of drugs that halted the progression of the HIV virus before it developed into AIDS was being used to treat patients. These antiretrovirals prolong life, but they are not a cure. To date, AIDS has taken more than 30 million lives worldwide. As AGT begins its trial for a cure for HIV/AIDS, here’s a closer look at the history of HIV cure research from the first days of HIV to the development of the antiretrovirals in use today.

Photo Credit: CDC

The L.A. Times and the San Francisco Chronicle immediately ran stories about the report. Within days, the CDC was notified of PCP (Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia) and other opportunistic infections, such as the rare and unusually aggressive cancer, Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS), among groups of gay men in New York and California.

The CDC formed the Task Force on Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Other Opportunistic Infections just three days after publication of the initial MMWR. The job of the Task Force was to identify risk factors for PCP and KS and develop a case definition for use across the country.

On July 3, the MMWR reported KS and PCP among 26 gay men in New York and California. The New York Times published an article, “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” on the same day.

back2stonewall.com

Discovering the Cause

By September 1981, the first Kaposi’s Sarcoma clinic opened in San Francisco as the number of reported cases in the U.S. climbed. It was assumed this new disease was limited to gay men until the first of those with hemophilia became infected through the blood supply. By the end of the year, there would be a total of 159 cases reported to date in the U.S.

By the Spring of 1982, it was estimated that tens of thousands of people might be affected by the new disease. The uncertainty over what caused this “Gay Cancer” and how it spread was a source of great anxiety for the public. On September 24, 1982, two significant events took place: the CDC defined and used the term AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) for the first time and Congress allocated $5 million to CDC for surveillance, with another $10 million allocated to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for AIDS research.

By the end of the year, there would be 771 cases reported to date in the U.S. with 618 deaths.

Congress Passes Funding Bill

On March 4, 1983, the MMWR suggested that a sexually transmitted agent or exposure to blood or blood products might cause AIDS. In May, the U.S. Congress passed the first bill that included specific funding for AIDS research and treatment. Agencies within the Department of Health and Human Services received $12 million. That same month, the Pasteur Institute in France reported the discovery of a retrovirus (LAV) that could be the cause of AIDS.

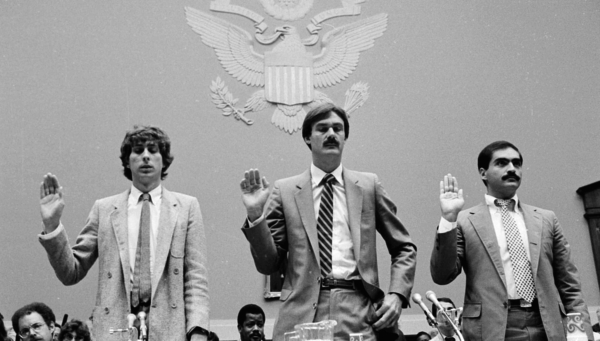

Three AIDS activists are sworn in before a House Governmental Relations subcommittee hearing on Capitol Hill to study strategies for dealing with the fatal disease, Aug. 2, 1983. From left to right: Michael Callen of New York, Roger Lyon of San Francisco, and Anthony Ferrara of Washington. AP. Photo Credit: The Atlantic

On September 9, 1983, the CDC MMWR identified all major routes of HIV transmission. The MMWR also ruled out transmission by casual contact, food, water, air, or surfaces. This information was comforting to the public. However, it did not alter the public’s fear of interaction with those who were infected. Realizing this, AIDS organizations pushed hard for a series of legal protections. In response to the global spread of HIV/AIDS, the World Health Organization (WHO) began international surveillance of the disease that November. Research into potential treatments for HIV/AIDS was taking place on a global scale.

By the end of the year, there would be 2,807 reported cases to date in the U.S. with 2,118 deaths.

Search for a Cure

Antiretrovirals

The first step in the search for an HIV cure was to identify the specific cause of HIV. By April of 1984, less than four years from the first reports of this new disease, HHS Secretary Margaret Heckler announced that Dr. Robert Gallo and his colleagues at the National Cancer Institute had identified a retrovirus, labeled HTLV-III, as the cause of AIDS. In conjunction with this finding, Heckler announced that a diagnostic blood test had been developed. It was now possible to test for HIV and inform those afflicted, but there was still no hope for long-term survival from this horrific disease.

By the end of the year, there would be 7,239 cases reported to date in the U.S. with 5,596 deaths

Many researchers focused on finding a way to keep the virus (HIV) from developing into full-blown disease (AIDS). They reasoned that this approach would prolong the life of those with the virus.

By the end of 1986, in the U.S. there had been 28,712 cases of AIDS reported to date with 24,559 deaths and there was intense pressure from the arts and gay communities to find a workable treatment. In 1987, the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), one of the largest HIV clinical trial organizations in the world, was founded to broaden the scope of the HIV Cure research efforts at the NIH. One of the first drugs they worked on as a way to halt HIV was AZT (azidothymidine), a drug initially developed to treat cancer. Researchers recognized that, while this antiretroviral could stop the progression of HIV, the use of a single drug would not do the trick because its efficacy diminished over time. By the end of 1988, the U.S. had 82,362 cases of AIDS reported to date with 61,816 deaths.

Photo Credit: World Health Organization (WHO)

In 1988, the Assistant Secretary for Health established the Office of AIDS Research (OAR), later codified into law, to provide increased coordination of efforts to defeat HIV/AIDS. 1988 also saw the first World AIDS Day bring attention to the role of “civil society” in mobilizing a global response to this global disease. By the end of 1989, there had been 117,508 cases of AIDS reported in the US with 89,343 deaths.

Effective Treatment but No Cure

In 1993, Congress passed the NIH Revitalization Act. This Act authorized OAR to:

- plan, coordinate, and evaluate HIV/AIDS research;

- set scientific priorities for the NIH research agenda; and

- determine budgets for all NIH HIV/AIDS research.

Despite the Act, the number of reported cases and deaths in the US and worldwide continued to rise as work on a more effective treatment or HIV cure continued. In 1996, researchers found that triple-drug therapy could suppress HIV long-term without loss of effectiveness. The number of Americans dying from AIDS dropped for the first time with a 23% decrease from 1995. The drop was attributed to the new antiretroviral treatment.

Internationally, the number of reported AIDS cases continued to soar. By 1999, the HIV infection rate had doubled since 1996 in over 27 countries. More than 95% of all of those infected with HIV lived in the developing world. Of the total deaths due to AIDS, 95% to date occurred in those nations. The lack of access to antiretrovirals spurs UNAIDS and the World Health Organization (WHO) to initiate the ‘3 by 5’ Initiative to provide antiretroviral treatment to 3 million people worldwide by the year 2005.

In 2004, the year AIDS-related deaths hit their peak, the United Nations reported a growing AIDS crisis in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. It was reported that 15 million children worldwide have lost one or both parents to HIV/AIDS. In the U.S., there had been 940,000 cases of AIDS reported to date with 529,113 deaths. In 2005, WHO and UNAIDS released a report showing that the number of people on HIV antiretroviral drugs in developing nations had more than tripled to 1.3 million since 2003. In 2007, UNAIDS initiated new surveillance methods and estimated that 33 million people worldwide were living with HIV/AIDS. More than 25 years of coordinated global effort had produced an effective treatment, yet there was still no HIV cure.

Keith Haring artwork © Keith Haring Foundation

Clinical Trial for an HIV Cure

One of the promising developments in the search for an HIV cure is AGT’s Phase 1 clinical trial to investigate the safety of AGT103-T, a single-dose, lentiviral vector-based gene therapy developed to eliminate HIV from the millions of people globally infected with the disease. AGT is dedicated to finding a functional HIV cure because, with the use of antiretrovirals, CEO Jeff Galvin says, “we see that the suffering hasn't ended at all. It's just gone underground. You can have a relatively normal lifespan, but they have actually just shown statistically that your lifespan is shorter. Your quality of life is also significantly lower. And the psychological impact of the whole thing essentially makes you feel like you have a life sentence that you're serving. Science moved it from a death sentence to a life sentence. But what we want to do is get these people ‘out of jail’ and truly free from the impact of their infections.”

Sources

International

Avert Global Info and Education on HIV and AIDS

amfAR HIV/AIDS: Snapshots of an Epidemic - reported cases

UNAIDS Global HIV/AIDS Statistics 2020 Fact Sheet

U.S.